11.7 Other Considerations

Entities should be mindful of other tax considerations that are not

directly related to or within the scope of the accounting literature on business

combinations, including those that address deconsolidation, a planned sale or

disposal of a business (either of which could trigger discontinued operations

presentation in the financial statements), the election of an acquiree to apply

pushdown accounting, and other reorganizations or mergers in contemplation of an IPO

or related transaction.

11.7.1 Deconsolidation

Although this chapter focuses on business combinations, entities must also

evaluate special considerations when accounting for transactions that cause

deconsolidation of subsidiaries. The deconsolidation of a subsidiary may result

from a variety of circumstances, including a sale of 100 percent of an entity’s

interest in the subsidiary. The sale may be structured as either a “stock sale”

or an “asset sale.” A stock sale occurs when a parent sells all of its shares in

a subsidiary to a third party and the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities are

transferred to the buyer.

An asset sale occurs when a parent sells individual assets (and liabilities) to

the buyer and retains ownership of the original legal entity. In addition, by

election, certain stock sales can be treated for tax purposes as if the

subsidiary sold its assets and was subsequently liquidated.

Upon a sale of a subsidiary, the parent entity should consider the income tax

accounting implications for its income statement and balance sheet.

11.7.1.1 Income Statement Considerations

ASC 810-10-40-5 provides a formula for calculating a parent entity’s gain or

loss on deconsolidation of a subsidiary, which is measured as the difference between:

-

The aggregate of all of the following:

-

The fair value of any consideration received

-

The fair value of any retained noncontrolling investment in the former subsidiary or group of assets at the date the subsidiary is deconsolidated or the group of assets is derecognized

-

The carrying amount of any noncontrolling interest in the former subsidiary (including any accumulated other comprehensive income attributable to the noncontrolling interest) at the date the subsidiary is deconsolidated.

-

-

The carrying amount of the former subsidiary’s assets and liabilities or the carrying amount of the group of assets.

11.7.1.1.1 Asset Sale

See Section

6.2.7.3.1.1 for guidance on the accounting for the gain

or loss on an asset sale and the resulting tax effects.

11.7.1.1.2 Stock Sale

See Section 6.2.7.3.1.2 for

guidance on the accounting for the gain or loss on a stock sale and the

resulting tax effects.

11.7.1.2 Balance Sheet Considerations

Entities with a subsidiary (or component) that meets the held-for-sale

criteria in ASC 360 should classify the assets and liabilities associated

with that component separately on the balance sheet as “held for sale.” The

presentation of deferred tax balances associated with the assets and

liabilities of the subsidiary or component classified as held for sale is

determined on the basis of the method of the expected sale (i.e., asset sale

or stock sale) and whether the entity presenting the assets as held for sale

is transferring the basis difference to the buyer.

Deferred taxes associated with the stock of the component

being sold (the outside basis differences7) should not be presented as held for sale in either an asset sale or a

stock sale since the acquirer will not assume the outside basis

difference.

11.7.1.2.1 Asset Sale

In an asset sale, the tax bases of the assets and

liabilities being sold will not be transferred to the buyer. Therefore,

the deferred taxes related to the assets and liabilities (the inside

basis differences8) being sold should not be presented as held for sale; rather, they

should be presented along with the consolidated entity’s other deferred

taxes.

11.7.1.2.2 Stock Sale

In a stock sale, the tax bases of the assets and

liabilities being sold generally are carried over to the buyer.

Therefore, the deferred taxes related to the assets and liabilities (the

inside basis differences9) being sold should be presented as held for sale and not with the

consolidated entity’s other deferred taxes.

11.7.2 Discontinued Operations

When an entity contemplates sale or disposition of a portion of its business,

this might cause the portion of the business to be presented as discontinued

operations. In this scenario, specific accounting considerations apply. Guidance

on discontinued operations is presented in other sections of this Roadmap:

-

See Section 3.4.17.2 for a discussion of recognition of a DTA related to a subsidiary presented as a discontinued operation.

-

See Section 7.2 for interim reporting implications of intraperiod tax allocation for discontinued operations.

11.7.3 Pushdown Accounting Considerations

As previously noted, when an entity obtains control of a business, a new basis of

accounting is established in the acquirer’s financial statements for the assets

acquired and liabilities assumed. Sometimes the acquiree will prepare separate

financial statements after its acquisition. Use of the acquirer’s basis of

accounting in the preparation of an acquiree’s separate financial statements is

called pushdown accounting.

In November 2014, the FASB issued ASU 2014-17, which

became effective upon issuance. This ASU gives an acquiree the option to apply

pushdown accounting in its separate financial statements when it has undergone a

change in control. See Appendix A of Deloitte’s Roadmap Business Combinations for

additional discussion regarding pushdown accounting.

11.7.3.1 Applicability of Pushdown Accounting to Income Taxes and Foreign Currency Translation Adjustments

ASC 740-10-30-5 indicates that deferred taxes must be “determined separately

for each tax-paying component . . . in each tax jurisdiction.” ASC 805-50

does not require an entity to apply pushdown accounting for separate

financial statement reporting purposes. However, to properly determine the

temporary differences and to apply ASC 740 accurately, an entity must push

down, to each tax-paying component, the amounts assigned to the individual

assets and liabilities for financial reporting purposes. That is, because

the cash inflows from assets acquired or cash outflows from liabilities

assumed will be reflected on the tax return of the respective tax-paying

component, the acquirer has a taxable or deductible temporary difference

related to the entire amount recorded under the acquisition method (compared

with its tax basis), regardless of whether such fair value adjustments are

actually pushed down and reflected in the acquiree’s statutory or separate

financial statements.

An entity can either record the amounts in its subsidiary’s books (i.e.,

actual pushdown accounting) or maintain the records necessary to adjust the

consolidated amounts to what they would have been had the amounts been

recorded on the subsidiary’s books (i.e., notional pushdown accounting). The

latter method can often make recordkeeping more complex.

Further, to the extent the reporting entity’s functional currency differs

from the currency in which an acquiree files its tax return, an entity must

convert the entire amount recorded under the acquisition method for a

particular asset or liability to the currency in which the tax-paying

component files its tax return (the “tax currency”) to properly determine

the (1) temporary difference associated with the particular asset or

liability and (2) the corresponding DTA or DTL (i.e., deferred taxes are

calculated in the tax currency and then translated or remeasured in

accordance with ASC 830).

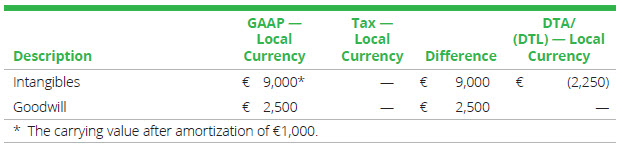

Example 11-30

Assume the following:

-

A U.S. parent acquires the stock of U.S. Target (UST), which owns Entity A, a foreign corporation operating in Jurisdiction X, in which the income tax rate is 25 percent.

-

Entity A must file statutory financial statements with X that are prepared in accordance with A’s local GAAP; the acquisition does not affect these financial statements or A’s tax basis in its assets and liabilities in X.

-

As a result of the acquisition, A will record a fair value adjustment of $10 million related to its intangible assets, which will be amortized for U.S. GAAP purposes over 10 years, the estimated useful life of the intangible assets, which was not recognized for statutory purposes.

-

Entity A’s functional currency and local currency is the euro. As of the date of acquisition, the conversion rate from USD to the euro was 1 USD = 1 euro. At the end of year 1, the conversion rate was 1.20 USD = 1 euro.

Entity A will record its intangible assets as part of

its statutory-to-U.S.-GAAP adjustments

(“stat-to-GAAP adjustments”) and will not be

entitled to any amortization deduction for local

income tax reporting purposes. However, the cash

flows related to such intangible assets will be

reported on A’s local income tax return

prospectively, and such cash flows will be taxable

in X. Thus, A must recognize a $2.5 million DTL as

part of its stat-to-GAAP adjustments related to the

excess of the intangible assets’ U.S. GAAP reporting

basis over its income tax basis. This DTL will

reverse as the intangible assets are amortized for

U.S. GAAP financial statement reporting purposes.

The year-end stat-to-GAAP adjustments and related

currency conversions (in thousands) are as

follows:

Example 11-31

Assume the same facts as in the

example above, except that Entity A has NOL

carryforwards of €10 million for which A has

recognized a €2.5 million DTA [€10 million NOL

carryforward × 25% tax rate]. On the reporting date,

A has significant objectively verifiable negative

evidence and has determined that the only available

source of future taxable income is the reversal of

existing DTLs.

Parent’s books, for A’s original business combination

journal entries, at the end of year 1 (in thousands)

are as follows:

Entity A’s DTL that is recorded on

the parent’s books represents an available future

source of income in the assessment of the

realization of A’s DTAs. Accordingly, A’s net DTA

(before valuation allowance) at the end of year 1 is

€0.25 million (€2.5 million NOL carryforward DTA –

€2.25 million intangibles DTL) or $0.30 million

(€0.25 million × 1.2); therefore, on the basis of

the evidence, a full valuation allowance will be

needed. Regardless of whether the journal entries

are actually or notionally pushed down, A’s net DTA

to be assessed for realizability should be the

same.

11.7.4 Other Forms of Mergers

11.7.4.1 Successor Entity’s Accounting for the Recognition of Income Taxes When the Predecessor Entity Is Nontaxable

In connection with a transaction such as an IPO, the

historical partners in a partnership (the “legacy partners”) may establish a

C corporation that will invest in the partnership at the time of the

transaction. In the case of an IPO, the C corporation is typically

established to serve as the IPO vehicle (i.e., it is the entity that will

ultimately issue its shares to the public) and therefore ultimately becomes

an SEC registrant. These transactions have informally been referred to in

the marketplace as “Up-C” transactions.

The legacy partners typically control the C corporation even

after the IPO (i.e., the legacy partners sell an economic interest to the

public while retaining shares with voting control but no economic interest).

The C corporation uses the IPO proceeds to purchase an economic interest in

the partnership along with a controlling voting interest. Accordingly, the C

corporation consolidates the partnership for book purposes. Because the C

corporation is taxable, it will need to recognize deferred taxes related to

its investment in the partnership. This outside basis difference is created

because the C corporation (1) receives a tax basis in the partnership units

that is equal to the amount paid for the units (i.e., fair value) but (2)

has carryover basis in the assets of the partnership for U.S. GAAP reporting

(because the transaction is a transaction among entities under common

control). See Appendix

B of Deloitte’s Roadmap Business Combinations for

further discussion of the accounting for common-control transactions.

Typically, the original partnership is the C corporation’s predecessor entity

and the C corporation is the successor entity (and the registrant). After

the transaction becomes effective, the registrant’s initial financial

statements reflect the predecessor entity’s operations through the effective

date and the successor entity’s post-effective operations in a single set of

financial statements (i.e., the predecessor and successor financial

statements are presented on a contiguous basis). Since no step-up in basis

occurs for financial statement purposes because of the common-control nature

of the transaction, the income statement and balance sheet are presented

without use of a “black line.” The equity statement, however, reflects the

recognition of a noncontrolling interest as of the effective date and

prospectively in the registrant’s post-effective financial statements. In

addition, the C corporation must recognize deferred taxes upon investing in

the partnership, which occurs on the effective date.

In such situations, questions often arise about whether (1) the predecessor

entity’s tax status has changed in such a way that the deferred tax benefit

or expense related to the recognition of the deferred tax accounts would be

accounted for in the income statement or (2) there has been a contribution

of assets among entities under common control, in which case the recognition

of the corresponding deferred tax accounts would be accounted for in

equity.

While the formation of the new C corporation has resulted in

a change in the reporting entity, we do not believe that the predecessor

entity’s tax status has changed. In fact, in the situation described above,

the predecessor entity was formerly structured as a partnership and

continues to exist as a partnership after the effective date (i.e., the

legacy partners continue to own an interest in the same entity, which

remains a “flow-through” entity to them both before and after the effective

date) even though the successor entity’s financial statements are presented

on a contiguous basis with the predecessor entity’s financial statements,

albeit with the introduction of a noncontrolling interest.

Accordingly, we believe that the recognition of taxes on the

C corporation’s investment in the partnership should be recorded as a direct

adjustment to equity, as if the former partners in that partnership

contributed their investments (along with the corresponding tax basis) to

the C corporation (see Section 12.4.1

for a discussion of why these adjustments are recorded as equity

transactions). The additional step-up in tax basis received by the C

corporation upon its investment in the partnership (and in the flow-through

tax basis of the underlying assets and liabilities of the partnership) after

the effective date would similarly be reflected in equity in accordance with

ASC 740-20-45-11(g), which states:

All changes in the tax bases of assets and

liabilities caused by transactions among or with

shareholders shall be included in equity including the

effect of valuation allowances initially required upon recognition

of any related deferred tax assets. Changes in valuation allowances

occurring in subsequent periods shall be included in the income

statement. [Emphasis added]

Example 11-32

F1 and F2 own LP, a partnership with net assets whose

book basis is $2,000 and fair value is $20,000. F1

and F2 have a collective tax basis of $1,000 in

their units of the partnership and a collective DTL

of $210. (Assume that the tax rate is 21 percent and

that the outside basis temporary difference will

reverse through LP’s normal operating

activities.)

F1 and F2 form Newco, a C corporation, which sells

nonvoting shares to the public in exchange for IPO

proceeds of $12,000. Newco records the following

journal entry:

Newco then uses the IPO proceeds to purchase 60

percent of the units of LP from F1 and F2. Because

Newco and LP are entities under common control,

Newco records a $2,000 investment in LP’s assets (at

F1’s and F2’s historical book basis as if the net

assets were contributed) along with a noncontrolling

interest of $800 (representing the units of LP still

held by F1 and F2) and a corresponding reduction in

equity of $10,800 for the deemed distribution to F1

and F2. This leaves $1,200 that is attributable to

the controlling interest (which also reflects the

book basis of Newco’s investment in the assets of

LP). Newco records the following journal entry:

If it is assumed that Newco is

subject to a 21 percent tax rate and that Newco’s

tax basis in the units has remained consistent with

F1’s and F2’s historical tax basis in LP, Newco will

also record a DTL of $126, which is calculated as

($1,200 book basis – $600 tax basis) × 21%, with an

offset to equity, as follows:

In other words, F1 and F2 have effectively

contributed their 60 percent investment in LP (along

with 60 percent of their corresponding DTL related

to LP) to Newco.

Because the sale of units of LP to

Newco is a taxable transaction, F1 and F2 would have

taxable income of $11,400 ($12,000 proceeds less tax

basis of the interest sold [60% of $1,000]),

resulting in taxes payable of $2,280 ($11,400 × 20%

capital gains rate). F1 and F2 would also eliminate

the portion of their collective DTL that was

effectively contributed to Newco, which is

calculated as ($2,000 book basis – $1,000 tax basis)

× 60% × 21%. Newco would receive a tax basis in the

units of LP that is equal to its purchase price of

$12,000 and would record a DTA of $2,268, which is

calculated as ($12,000 tax basis – $1,200 book

basis) × 21%, ignoring realizability

considerations.

In accordance with ASC 740-20-45-11(g), Newco’s

change in deferred taxes as a result of a change in

its tax basis in its investment in LP would be

recorded directly in equity as follows:

11.7.4.2 Accounting for the Elimination of Income Taxes Allocated to a Predecessor Entity When the Successor Entity Is Nontaxable

In connection with certain transactions such as an IPO, a

parent may plan to contribute the “unincorporated” assets, liabilities, and

operations of a division or disregarded entity to a new company (i.e., a

“newco”) at or around the time of the transaction. The newco is typically

established to serve as the IPO vehicle (i.e., it is the entity that will

ultimately issue its shares to the public) and therefore ultimately becomes

an SEC registrant. In some instances, income taxes will be allocated in the

financial statements of the predecessor division or disregarded entity in

periods before the IPO, but the successor newco will be a nontaxable entity

after the IPO. See Deloitte’s Roadmap Initial

Public Offerings for additional guidance around the

identification of and reporting by predecessor and successor entities.

Typically, the division or disregarded entity is determined to be the newco’s

predecessor entity and the newco is determined to be the successor entity.

After the transaction is effective, the successor’s initial financial

statements reflect the predecessor entity’s operations through the effective

date and the successor entity’s operations after the effective date in a

single set of financial statements (i.e., the predecessor and successor

financial statements are presented on a contiguous basis). Since no step-up

in basis occurs for financial statement purposes because of the

common-control nature of the transaction, the income statement and balance

sheet are typically presented without the use of a “black line.”

A predecessor entity’s financial statements that have been

filed publicly often include an income tax provision. SAB Topic 1.B.1

requires that members (i.e., corporate subsidiaries) and certain

nonmembers10 (i.e., divisions or lesser business components of another entity) of a

group that are part of a consolidated tax return include an allocation of

taxes when those members or nonmembers issue separate financial

statements11 In addition, an entity may have a policy to allocate taxes to the

separate financial statements of legal entities that are not subject to tax

and are disregarded by the taxing authority (e.g., single-member LLCs or

disregarded entities).12 When the successor entity is nontaxable (e.g., a master limited

partnership), however, the successor entity will need to eliminate (upon

effectiveness) any deferred taxes that were previously allocated to the

predecessor entity.13

In situations in which deferred income taxes that were allocated to the

predecessor entity are eliminated in the successor entity’s financial

statements when the successor entity is nontaxable, questions often arise

about whether (1) the predecessor entity’s tax status has changed in the

manner discussed in ASC 740-10-25-32 such that the deferred tax

benefit/expense from the elimination of the deferred tax accounts would be

accounted for in the income statement, as prescribed by ASC 740-10-45-19, or

(2) the deferred taxes were effectively retained by the contributing entity,

suggesting that the deferred taxes should be eliminated through equity.

As noted above, while the predecessor entity has received an allocation of

the parent’s consolidated income tax expense, the predecessor entity

typically comprises unincorporated or disregarded entities that are not

individually considered to be taxpayers under U.S. tax law (i.e., the

historical owner was, and continues to be, the taxpayer). Accordingly, we do

not believe that the predecessor entity’s tax status has changed in the

manner discussed in ASC 740-10-25-32. Rather, we believe that the parent has

retained the previously allocated deferred taxes (which is consistent with

removing the deferred taxes through equity). Alternatively, the removal of

the net deferred tax accounts, particularly in the case of a net DTL, might

be analogous to the extinguishment (by forgiveness) of intra-entity debt.

ASC 470-50-40-2 provides guidance on such situations, noting that

“extinguishment transactions between related entities may be in essence

capital transactions.” Accordingly, we believe that it is appropriate to

reflect the elimination of deferred income taxes that were allocated to the

predecessor entity as a direct adjustment to the successor entity’s equity

on the effective date of the transaction.

The elimination of deferred taxes via an adjustment to

equity is also consistent with an SEC staff speech by Associate Chief

Accountant Leslie Overton in the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance at

the 2001 AICPA Conference on Current SEC Developments. Ms. Overton discussed

a fact pattern in which the staff believed that certain operations that

would be left behind upon a spin-off (i.e., retained by the parent) still

needed to be included in the historical carve-out financial statements of

the predecessor entity to best illustrate management’s track record with

respect to the business operations being spun. However, Ms. Overton

concluded her speech by noting that “[a]ssets and operations that are

included in the carve-out financial statements, but not transferred to Newco

should be reflected as a distribution to the Parent at the date Newco is

formed.”

11.7.4.3 Change in Tax Status as a Result of a Common-Control Merger

A common-control merger occurs when two legal entities that

are controlled by the same parent company are merged into a single entity.

Such a transaction is not a business combination because there was not a

change in control of the entities involved (i.e., they are controlled by the

same entity before and after the merger). The accounting for a change in an

entity’s taxable status through a common-control merger may differ from the

method described in the previous section. For example, an S corporation

could lose its nontaxable status when acquired by a C corporation in a

transaction accounted for as a merger of entities under common control. When

an entity’s status changes from nontaxable to taxable, the entity should

recognize DTAs and DTLs for any temporary differences that exist as of the

recognition date (unless these temporary differences are subject to one of

the recognition exceptions in ASC 740-10-25-3). The entity should initially

measure those recognizable temporary differences in accordance with ASC

740-10-30 and record the effects in income from continuing operations under

the guidance in ASC 740-10-45-19.

Although the transaction was between parties under common control, the

combined financial statements should not be adjusted to include income taxes

of the S corporation before the date of the common-control merger. ASC

740-10-25-32 states that DTAs and DTLs should be recognized “at the date

that a nontaxable entity becomes a taxable entity.” Therefore, any periods

presented in the combined financial statements before the common-control

merger should not be adjusted for income taxes of the S corporation.

However, it may be appropriate for an entity to present pro forma financial

information, including the income tax effects of the S corporation (as if it

had been a C corporation), in the historical combined financial statements

for all periods presented. For more information on financial reporting

considerations, see Section 14.7.1.

Footnotes

7

See Section 11.3.1 for the meaning

of “inside” and “outside” basis differences.

8

See footnote 7.

9

See footnote 7.

10

See Section 8.2.4 for a discussion

of the allocation of income taxes to divisions, branches, or lesser

components of the parent reporting entity.

11

See Section 8.3 for guidance on

acceptable methods of allocating income taxes to members of a

group.

12

See Section 8.2.3 for a discussion

of the allocation of income taxes to legal entities that are both

not subject to tax and disregarded by the taxing authority.

13

If the parent actually contributes a member

(corporate subsidiary) to a nontaxable successor entity and the

successor entity will continue to own that C corporation, previously

allocated deferred taxes would not be eliminated and this guidance

would not be applicable. However, such situations are rare.